The word pocket is derived from the Old Northern French word “poque,” which meant bag. And up through the 19th

century, if you looked up “pocket” in a dictionary, you would see it

defined as “a small pouch or bag attached to or inserted in a garment.”

The word pocket is derived from the Old Northern French word “poque,” which meant bag. And up through the 19th

century, if you looked up “pocket” in a dictionary, you would see it

defined as “a small pouch or bag attached to or inserted in a garment.”

Ferdinand

II, Archduke of Further Austria, wears a proto-“pocket” — a bag hung

from a belt or tied around the body. He’s also rockin’ a pretty sweet

codpiece.

This is because the original pockets weren’t like the sewn-in pockets

we know today, but rather separate bags detached from clothing. From

the 15

th until the mid-16

th century, men and women

carried essential items and currency in a pouch that was typically tied

around the waist or hung from a belt.

As thieves and “cutpurses” became

more of a problem in the 17

th century, people began to cut

slits in their shirts, skirts, and pants, and tuck their pouches inside

their clothing for safekeeping. This practice necessitated making the

bags flatter and easier to reach into, so they would be more

accessible and not create a significant bulge.

The names of the various things men carried in these tucked-away

pouches were hyphenated with “pocket” to create a moniker that described

their small size and portable nature. For example:

- Pocket-handkerchief

- Pocket-knife

- Pocket-brandy (flask)

- Pocket-pistol (Often a single-shot derringer-type gun. Also used to mean flask.)

- Pocket-money

- Pocket-book (While today “pocketbooks” mean lady’s handbags, a man’s

pocket-book at this time was a small leather notebook-like case used

for carrying papers, diary entries, notes, etc.)

As men’s garments became more form-fitting, it became harder to fit a

pocket purse between clothing and body. The next obvious step then was

to attach the pouches to the clothing itself, and tailors began to sew

pocket bags into the seams of men’s breeches, and then into their coats.

In the 18

th century, pockets were added to vests, and in the

1900s, many kinds of men’s garments began to include a wide range of

pockets: inside/outside breast pocket, watch pocket, side/hip pants

pocket, ticket pocket, etc.

Pickpockets loved the new trend towards men wearing garments with sewn-in pockets. It made it easier to steal their possessions!

For their part, women continued to carry pouches under their

billowing dresses through the late 1800s. Accessed through a placket

hole in the back of the skirt, these sort of internal, reverse fanny

packs proved popular with pickpockets, and it became common for women to

carry a small drawstring reticule in their hand instead. Attached

pockets made their way into some women’s garments, but never quite took

off as they did for men, as the more fitted fashions of the 20

th

century precluded their possibility — lest they ruin the line of the

clothes. Women thus largely returned to using outside pockets – i.e.,

purses and handbags — while men embraced the use of inside, attached

pockets. Thus the modern association of bags-and-women, pockets-and-men.

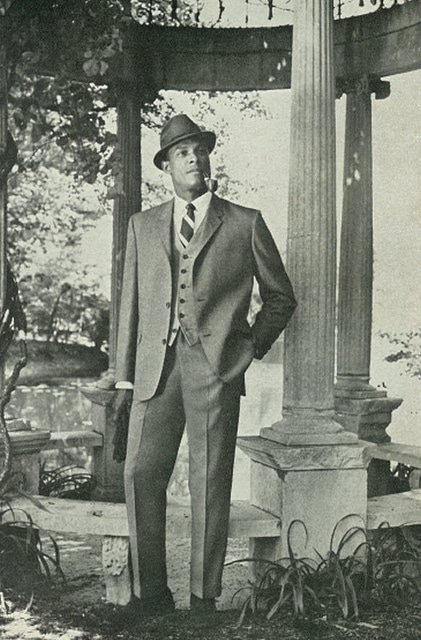

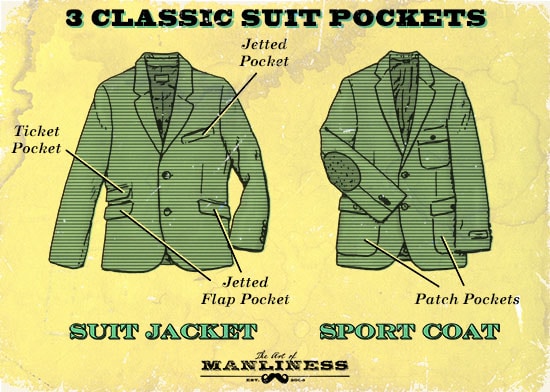

Adding Functionality to Style: 3 Classic Suit Pockets

Early pocket options on pants were fairly limited and

straightforward: they were created in the waistband, straight across the

top, or on the sides. The jacket was where more experimentation took

place, and the choice of pockets indicated its level of formality; the

general rule was (and is), that the more external layers of fabric —

i.e. more pockets — the less sleek and sharp the garment, and the less

formal it is. There are 3 classic suit pockets that were popular in yesteryear, and continue to adorn suits today:

Jetted Pockets.

Jetted Pockets. The first jacket pockets were sewn

inside the lining or seams of garments, and are called “jetted” pockets.

In their simplest form, they consist of little more than a slit; if you

look at the left breast of your suit jacket, you’ll likely see an

example. Jetted pockets can also have flaps, and this is what you’ll

probably see on the bottom hip pockets of your jacket. These flaps came

into vogue at the beginning of the 20

th century and were

originally designed to protect the contents of the inner pouch from

falling out and from getting wet with rain. When you went inside, and

the flap was no longer in use, you tucked it into your pocket; this

tradition is of course no longer practiced, and the flap is kept

perennially outside the jacket. Suits that are the most formal,

especially tuxedos, do away with flap pockets altogether to give the

piece a more streamlined look.

Ticket Pockets.

Ticket Pockets. Another popular inside jacket pocket

was the ticket pocket. Sitting above the right hip pocket, and about

half the size, its purpose is easily guessed: it held a gentleman’s

train ticket when he traveled by rail. In the 20

th century it

became known as a change or cash pocket, and it communicated that your

suit had been custom tailored. Still today, few off-the-rack suits come

with a ticket pocket, and they often must be specially ordered.

Patch pockets first adorned hunting and sporting jackets.

Patch Pockets. When gents of the 19

th

century desired additional pockets for storing their odds and ends while

out in the countryside, tailors began adding patch pockets to their

sport coats.

A patch pocket consists of a piece of fabric sewn to the outside of a

garment, forming one side of the pocket, with the other side formed by

the material of the garment itself.

Patch pockets can have pleats that expand their capacity and flaps to

protect their contents. The sporting men of yesteryear used them for

storing provisions, cartridges, and various other supplies when hunting,

shooting, riding horses, cycling, and playing golf and polo. Patch

pockets were also adopted by that other quintessentially Victorian

English type: the explorer.

Safari jackets were outfitted with numerous pockets for storing one’s gun cartridges, field glasses, pipe, matches, notebook, etc.

Because they added an extra layer of fabric to a garment, patch

pockets were considered the least formal kind of pocket, and still today

are generally considered only appropriate for sport coats, rather than

blazers or suit jackets. (

What to know more about the differences between these three jackets? Click here.)

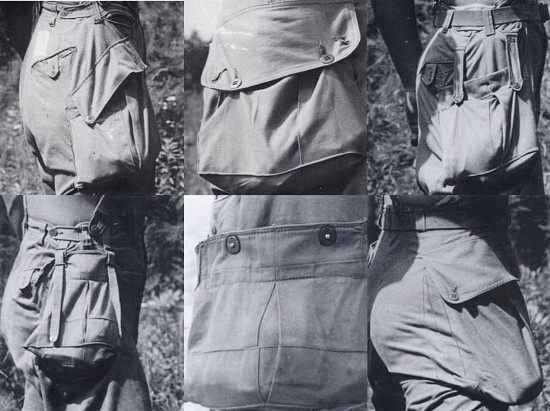

The Utilitarian: The Cargo Pocket

Patch pockets, with their rugged functionality, were unsurprisingly

adopted by the military for both shirts and jackets. But it wasn’t until

the 20

th century that the pocket would migrate south,

attaching itself to men’s pants, expanding in size, and becoming known

as the famous cargo pocket.

The British were the first to introduce the pants cargo pocket. In

1938, they adopted a revolutionarily functional and practical combat

uniform dubbed “Battledress.” Battledress trousers came with a large map

pocket positioned in the front by the left knee, and a right upper hip

pocket that held a field dressing for first aid.

The cargo pocket was introduced to the States by Major William P.

Yarborough, a commander in the 82nd Airborne Division. Dissatisfied with

the current paratrooper jump suit — which consisted of a one-piece

coverall worn over a regular infantry dress — Yarborough set out to

create a uniform that would be more functional for their unique mission

and distinguish the airborne forces from other soldiers. Yarborough

developed special jump boots, as well as a fatigue uniform that included

extra large pockets on both top and bottom — 4 on the jacket, 2 on the

pants.

The breast pockets were slanted down and towards the center to give

the paratrooper easier access when he was wearing his parachute harness,

and the cargo thigh pockets expanded to hold ample supplies. The

jacket’s collar also included a unique hidden dual-zippered knife

pocket, which held a 3-inch switchblade. Should the jumper become caught

in a tree, the knife could be used to cut himself free of parachute

lines and the harness itself, though he was trained to employ it as a

weapon as well. Some paratroopers also used the knife to cut a section

from the parachute’s fabric, to be turned into a souvenir scarf

commemorating the mission.

A paratrooper already shouldered 100lbs of equipment, and the jump

suit’s pockets were handy for holding all the things that couldn’t be

fit into the other bags and belts he had strapped to him. Pockets were

often stuffed with socks, rations, and grenades, and the average

paratrooper carried about 9lbs of gear in them.

Paratroopers’ pockets were in fact so heavy laden, that when they

jumped on D-Day, the shock of the chute opening ripped the seams of the

pockets open, spilling their contents all over Normandy. The

paratroopers reinforced the seams with patches on subsequent jumps.

During

WWII, the military experimented with a wide variety of cargo pocket

designs. Some of the pockets were so big, and carried so much gear, that

suspenders were necessary to keep the soldier’s pants up.

The design they eventually chose for the M-1943 uniform was unfortunately hard for the solider to access.

The Army, seeing the utility of the paratrooper jump suit, issued a

new uniform in 1943 for the rest of its troops that included trousers

with two large cargo pockets worn on the side. These cargo pockets were

discontinued a few years later, and replaced with front patch pockets.

They wouldn’t be re-introduced until the 1960s, when none other than

William Yarborough (now a lieutenant general), redesigned the military’s

jungle fatigues for combat in Vietnam.

After a hiatus, cargo pant pockets returned to combat fatigues during the Vietnam War.

Drawing inspiration from the old paratrooper uniforms, he created a

jacket with 4 large pockets, and trousers with 7, including two side

cargo pockets. There was even a pocket within the left cargo pocket —

though what it was supposed to be used for remained a mystery to the

men. It was intended for a survival kit that was never issued; soldiers

instead used it for cigarettes and small mementos.

Today’s Army Combat Uniform (ACU) includes 5 pockets in the blouse, and 8 in the pants.

In the modern day, cargo pockets have of course found their way into

civilian dress — becoming a ubiquitous part of men’s shorts and pants.

But given the rule of thumb mentioned above — the more pockets a garment

has, the less sleek/formal it is — it’s inadvisable to don cargo pants

and shorts in situations where you want to appear more sharp and

stylish. Pockets add bulk to a garment, even when they aren’t filled,

and appear quite bulky and misshapen once packed with odds and ends.

Cargo shorts and pants are thus best worn as intended — as functional

attire for tactical, outdoor, and sporting pursuits.

Bags Vs. Pockets in the Modern Day

Given the rich history of the humble pocket, it’s not surprising

we’ve become so attached to their attachment. Men’s pockets have for

centuries held the components of millions of adventures and memorable

moments: the handkerchief offered to a sad, but darn cute lady; the

money used to buy a favorite book; the ticket for a cross-country

adventure; the knife that saved a life.

Pockets represent the ultimate in functionality and minimalism. What

you need is right at hand. And if you can’t fit it into your pockets,

you have to do without it. (And if it turns out you needed that

something after all, well, now you just get to practice

the manly art of improvisation!)

This lack of fussiness likely has much to do with the persistence of

pockets’ popularity amongst men, and the fact that, at least in America,

the externally carried bag has yet to make a comeback.

Ridicule around “murses” is a bit much though, in my opinion. We’re

in a cultural place where a man can carry a medium to large bag, or

whatever fits in his pockets, but nothing in-between. Which is a little

odd when you think about it. Yet I think I do understand the philosophy

behind this mentality. You either travel super light and nimbly, or

you’re full-on prepared, with the kind of gear and essentials you’ll

need a full-sized daypack to carry. I don’t know if this mindset is

completely rational, but it makes its own kind of manly sense.

With that in mind, next month we’ll be running a post on what you

might consider carrying from day to day (the art of EDC!), and later in

the year we’ll devote primers to some of mankind’s favorite carryalls,

such as the messenger, the briefcase, and the satchel.